Seems the last couple of times I have tested the darkroom safelight I have had to cut down the illumination. That should be a clue that the filters are fading and it is time to replace them. We use a Thomas Duplex Super Safelight that I rebuilt many years ago. Since we have a small darkroom I knew I needed to attenuate the light. My original safelight was modified when I rebuilt it and the 35 watt lamp was replaced with a 18 watt lamp. Note: You have to replace the ballast and start capacitor if you change the lamp wattage. Wasn’t that big a problem seeing how the original ballast was no good. I purchase the safelight many years ago not working for little to nothing.

Seems the last couple of times I have tested the darkroom safelight I have had to cut down the illumination. That should be a clue that the filters are fading and it is time to replace them. We use a Thomas Duplex Super Safelight that I rebuilt many years ago. Since we have a small darkroom I knew I needed to attenuate the light. My original safelight was modified when I rebuilt it and the 35 watt lamp was replaced with a 18 watt lamp. Note: You have to replace the ballast and start capacitor if you change the lamp wattage. Wasn’t that big a problem seeing how the original ballast was no good. I purchase the safelight many years ago not working for little to nothing.

So, now I needed to replace the filters. Since I am only interested in B&W, work that simplifies things for sure. All I need to find is the correct filter and then I can assemble my own replacement. I have plenty of scrap glass, and tape.

With a little research on the Internet I discovered that the hard part had already been done. Seems a Rosco #19 “Fire” filter has the necessary bandwidth to filter out the annoying green and blue spikes in the low pressure sodium lamp spectrum. And, seems that others had proven this the best way possible. . . they tested it in their own darkroom.

All I needed was to order some filter material. Rosco filters are the industry standard for stage and film production and readily available. That was way too easy. The thing that I was still toying with was how to adjust the light output. It finally came to me. Why not put the #19 filter in the body position and then add a Neutral Density filter to the vane? Yep, that would do it. So I ordered a sheet of Rosco #19 filter and a sheet of 0.30 ND.

We have a lot of scrap glass around. I cut new glass to fit the body and vanes using TruVue Conservation Grade UV glass. Thought it wouldn’t hurt to add even more filtration. I also found out why the factory uses tissue paper. Without it, the filter material does not look that great against the glass and I could see that if any moisture were to condense in there, it could be bad for the filter. I really didn’t want to use tissue paper and I had a roll of Gila frosted window film from another project. This stuff is a self-adhesive plastic material used to frost windows. It was exactly what I needed to put a smooth textured surface on the inside of the glass to keep the filter from sticking. It also works well to diffuse the light.

One of my favorite tapes is the aluminum HVAC ducting tape. It is lightproof, sticks and stays in place. Slit a few pieces of tape, peel the backing and it will hold the filter sandwich in place with ease.

I have to admit that I am a contact printer. Susan and I both contact print. There seems to be some confusion about contact printing and all I can say is, it is the easiest way you can make a print. Contact printing is nothing more than laying the negative directly on a sheet of printing paper, covering it with a piece of glass, and adding some light for the exposure. Nothing could be more simple. You do not need any special equipment to print on graded paper. A negative, some graded paper, a sheet of glass, and a lamp.

I have to admit that I am a contact printer. Susan and I both contact print. There seems to be some confusion about contact printing and all I can say is, it is the easiest way you can make a print. Contact printing is nothing more than laying the negative directly on a sheet of printing paper, covering it with a piece of glass, and adding some light for the exposure. Nothing could be more simple. You do not need any special equipment to print on graded paper. A negative, some graded paper, a sheet of glass, and a lamp. Strange how many questions we get about what we do, why we do it, and always how do you do certain things. I never mind answering questions. This is how one learns, and I feel that sharing what you know is very important. We have no secrets. . . no secret methods. . . secret places. . . secret formulas. . . or anything that is in any way secret.

Strange how many questions we get about what we do, why we do it, and always how do you do certain things. I never mind answering questions. This is how one learns, and I feel that sharing what you know is very important. We have no secrets. . . no secret methods. . . secret places. . . secret formulas. . . or anything that is in any way secret.

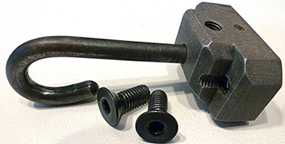

We tend to photograph in remote locations. We are always climbing over rocks, and are knee deep in mud or snow. One of the first packs I used was a really well-made and versatile Art Wolfe design that was perfect for a 4×5. The pack had a small webbing loop at the top and I soon found myself hooking it to one of the knobs on my Zone VI tripod. Worked great!

We tend to photograph in remote locations. We are always climbing over rocks, and are knee deep in mud or snow. One of the first packs I used was a really well-made and versatile Art Wolfe design that was perfect for a 4×5. The pack had a small webbing loop at the top and I soon found myself hooking it to one of the knobs on my Zone VI tripod. Worked great! a challenge. When I need to think about something, I usually take a nap. I do my best thinking when asleep.

a challenge. When I need to think about something, I usually take a nap. I do my best thinking when asleep.

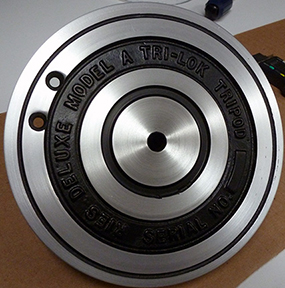

I have added this modification to both our ‘J’ and ‘A’ model Ries tripods and they have preformed flawlessly for years. Ries tripods are extremely well-made and will support well beyond their factory weight ratings. I have hung a 45 plus-pound pack from my ‘A’ model for years now and never had any issues. . . except sometimes heaving that heavy pack onto the hook when in a difficult position.

I have added this modification to both our ‘J’ and ‘A’ model Ries tripods and they have preformed flawlessly for years. Ries tripods are extremely well-made and will support well beyond their factory weight ratings. I have hung a 45 plus-pound pack from my ‘A’ model for years now and never had any issues. . . except sometimes heaving that heavy pack onto the hook when in a difficult position. I have always been an advocate of vertical integration. The more you can do yourself, the better control you have of the outcome. For many years I used prepackaged photo chemicals and have never had a problem. But, as the traditional darkroom and the materials used become more and more an alternative process, commercially available photo chemicals are getting harder to find. Some favorite chemicals have vanished. An old favorite, the Zone VI line of print developer, fixer and hypo are now gone from Calumet. I recently witnessed 8 bags of print developer and 2 bags of print and film fixer selling for $127.50 on eBay. That is well over double the original cost from Calumet.

I have always been an advocate of vertical integration. The more you can do yourself, the better control you have of the outcome. For many years I used prepackaged photo chemicals and have never had a problem. But, as the traditional darkroom and the materials used become more and more an alternative process, commercially available photo chemicals are getting harder to find. Some favorite chemicals have vanished. An old favorite, the Zone VI line of print developer, fixer and hypo are now gone from Calumet. I recently witnessed 8 bags of print developer and 2 bags of print and film fixer selling for $127.50 on eBay. That is well over double the original cost from Calumet.

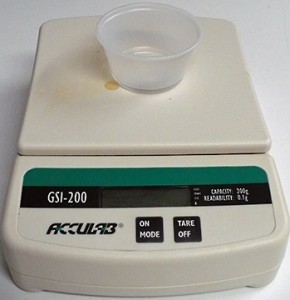

As I said before, for me, mixing photo chemicals is nothing less than following a recipe.

As I said before, for me, mixing photo chemicals is nothing less than following a recipe.

I use distilled water for all stock solutions. I always use distilled water for stock solutions and processing film. Unless your tap water has known problems, it should be fine for mixing printing chemicals.

I use distilled water for all stock solutions. I always use distilled water for stock solutions and processing film. Unless your tap water has known problems, it should be fine for mixing printing chemicals.