Darkroom

THOMAS DUPLEX SUPER SAFELIGHT FILTERS

Seems the last couple of times I have tested the darkroom safelight I have had to cut down the illumination. That should be a clue that the filters are fading and it is time to replace them. We use a Thomas Duplex Super Safelight that I rebuilt many years ago. Since we have a small darkroom I knew I needed to attenuate the light. My original safelight was modified when I rebuilt it and the 35 watt lamp was replaced with a 18 watt lamp. Note: You have to replace the ballast and start capacitor if you change the lamp wattage. Wasn’t that big a problem seeing how the original ballast was no good. I purchase the safelight many years ago not working for little to nothing.

Seems the last couple of times I have tested the darkroom safelight I have had to cut down the illumination. That should be a clue that the filters are fading and it is time to replace them. We use a Thomas Duplex Super Safelight that I rebuilt many years ago. Since we have a small darkroom I knew I needed to attenuate the light. My original safelight was modified when I rebuilt it and the 35 watt lamp was replaced with a 18 watt lamp. Note: You have to replace the ballast and start capacitor if you change the lamp wattage. Wasn’t that big a problem seeing how the original ballast was no good. I purchase the safelight many years ago not working for little to nothing.

So, now I needed to replace the filters. Since I am only interested in B&W, work that simplifies things for sure. All I need to find is the correct filter and then I can assemble my own replacement. I have plenty of scrap glass, and tape.

With a little research on the Internet I discovered that the hard part had already been done. Seems a Rosco #19 “Fire” filter has the necessary bandwidth to filter out the annoying green and blue spikes in the low pressure sodium lamp spectrum. And, seems that others had proven this the best way possible. . . they tested it in their own darkroom.

All I needed was to order some filter material. Rosco filters are the industry standard for stage and film production and readily available. That was way too easy. The thing that I was still toying with was how to adjust the light output. It finally came to me. Why not put the #19 filter in the body position and then add a Neutral Density filter to the vane? Yep, that would do it. So I ordered a sheet of Rosco #19 filter and a sheet of 0.30 ND.

We have a lot of scrap glass around. I cut new glass to fit the body and vanes using TruVue Conservation Grade UV glass. Thought it wouldn’t hurt to add even more filtration. I also found out why the factory uses tissue paper. Without it, the filter material does not look that great against the glass and I could see that if any moisture were to condense in there, it could be bad for the filter. I really didn’t want to use tissue paper and I had a roll of Gila frosted window film from another project. This stuff is a self-adhesive plastic material used to frost windows. It was exactly what I needed to put a smooth textured surface on the inside of the glass to keep the filter from sticking. It also works well to diffuse the light.

One of my favorite tapes is the aluminum HVAC ducting tape. It is lightproof, sticks and stays in place. Slit a few pieces of tape, peel the backing and it will hold the filter sandwich in place with ease.

I placed the #19 filter in the body and 0.30 ND in the vanes. My first test showed there was still too much light. I was testing at my closest point to the safelight for the worst case situation. I ended up adding a second layer of 0.30 which made for 0.60 ND, which is two full stops attenuation. But remember, I was testing with the most sensitive VC paper we use at a very close proximity to the safelight. Always test for the very worst case scenario.

Once finished, I found that the darkroom is much brighter than before. This proves that the filters do fade. Now we are back in business. With the vanes fully closed all VC and standard papers are safe. I like to print on Azo, which allows me to open the vanes for even more light.

I will test again in a year or so and if I need new filters they are easily replaced. I have plenty of material, the Rosco filter comes in a 24 x 24 inch square. Enough for several more safelight filters, if and when they are needed.

JB

CONTACT PRINTING & AZO

I have to admit that I am a contact printer. Susan and I both contact print. There seems to be some confusion about contact printing and all I can say is, it is the easiest way you can make a print. Contact printing is nothing more than laying the negative directly on a sheet of printing paper, covering it with a piece of glass, and adding some light for the exposure. Nothing could be more simple. You do not need any special equipment to print on graded paper. A negative, some graded paper, a sheet of glass, and a lamp.

I have to admit that I am a contact printer. Susan and I both contact print. There seems to be some confusion about contact printing and all I can say is, it is the easiest way you can make a print. Contact printing is nothing more than laying the negative directly on a sheet of printing paper, covering it with a piece of glass, and adding some light for the exposure. Nothing could be more simple. You do not need any special equipment to print on graded paper. A negative, some graded paper, a sheet of glass, and a lamp.

As a side note at this point, note I use the term LAMP. I have been corrected for years by an old friend that worked in the lighting industry at one time. In the industry, there is no such thing as a Light Bulb. . . it is a LAMP. So when I say LAMP, you can be assured that to the laymen I am talking about a Light Bulb. Now back to contact printing.

You can contact print on any paper, but one of the more interesting papers that is highly sought after is the old Kodak Azo. Azo is a silver chloride printing paper that was manufactured primarily for making proofs. It is extremely slow and requires such a large amount of light to yield an image it is mostly used as a contact printing paper. There seems to be some confusion about printing on Azo, and believe me, it is not that complicated. You just have to use a light source that is bright enough to yield reasonable printing times. This is where the lamp comes in.

All you need for printing on Azo is a simple, frosted lamp. For small negatives, 4×5 or smaller you can use a sheet of thick glass for printing. Larger negatives require a printing frame that holds the paper and negative under pressure. Edward Weston printed most of his most famous work using an 8×10 negative in a simple spring back printing frame, exposed under a lamp hanging by its cord from the ceiling. He adjusted the lamp intensity by changing the lamp size, or moving the lamp up and down by coiling the cord and using a clothespin.

So, now we get down to designing a printing rig for Azo. This can be as simple or complicated as you wish. I am going to describe how we print Azo and other papers. This is the setup we use, and how it is designed. I will say this again, you can use this same setup for contact printing regular enlarging paper also.

Let’s begin with the printing frame. We print large negatives, and we use a vacuum frame. The advantage of a vacuum frame is that you get absolute even pressure between the film and paper, no matter what the size of the film. We shoot 8×10, 11×14, 8×20 and 16×20 film, and have a vacuum frame large enough to accommodate the largest film. The vacuum frame is positioned under the drop table below the 8×10 enlarger. The vacuum pump is located just below the frame and includes a vacuum gauge which is handy to confirm the frame is properly closed and the vacuum is drawn down. By having the vacuum frame located below the enlarger we can also use the enlarger for printing on other papers, including VC papers that require control of blue and green light. The top of the counter is removable, as is the drop shelf which is used for enlarging. By removing the counter top and drop shelf, the vacuum frame is exposed and can be used for printing.

Printing on Azo only requires a lamp placed at some distance from the film and paper. Different negatives require different amounts of light. We set the vacuum frame to lamp reflector to a fixed distance and change the lamp wattage as required. The higher the wattage, the brighter the lamp. We keep a supply of lamps, ranging from 7 ½ watt to 200watt depending on the amount of light required. For most of our negatives we use the 45watt, 65watt, and sometimes a 100watt lamp. I like having a reflector around the lamp to help keep the light out of my eyes while printing. It also focuses the light downward onto the printing frame.

The lamp fixture is fitted with a custom machined clamping mechanism that attaches to the focusing rail of the Beseler 8×10 enlarger just below the lens, and is held in place with a thumbscrew. The enlarger head is raised or lowered to set the distance from the lamp reflector to the vacuum frame. We always adjust the lip of the reflector to vacuum glass to 30 inches. For our setup, this allows for even illumination of the vacuum frame and keeps the reflector between your eyes and the lamp. The lamp assembly is easily removed by loosening the thumb screw in case you want to change to enlarging paper and use the enlarger as a light source. This all sounds complicated, but in reality it is very simple. Refer to the photos for more detail.

The only thing that might affect your printing repeatability would be any variation of the line voltage to the lamp, which will affect the lamp output. The voltage is easily stabilized using a constant voltage transformer. You can find constant voltage units used, take a look on eBay. The one we use is a 350watt unit made by Sola-HD and will easily handle our largest lamp which is 200watts.

The constant voltage transformer is mounted in a large box that is located behind the 8×10 enlarger. I have also added a timer and a one second metronome, both made from an old digital alarm clock. Some cheap digital clocks can be modified to function as a resettable timer. I was able to rig the alarm beeper so that it chirps every second. I like to use a metronome when contact printing, and there is also a large digital readout timer that I can use as a check, just in case I lose count. The printing lamp and timer are wired to a foot switch. When you step on the switch the lamp comes on and the timer begins to count upward. The metronome runs continuously and has a switch to disable it. My wife does not like it, she only uses the timer. There is also a switch on the main box that controls the vacuum pump. As a safety precaution, the lamp will not activate until the vacuum pump is running. This way if you accidentally step on the footswitch with your box of paper open, the lamp will not light.

Printing is extremely simple. Switch off the room lights, place a sheet of printing paper, sandwiched with your negative, in the center of the vacuum frame. Close the glass top. Hit the pump switch and check to see that the frame has drawn down. When you are ready to start, step on the footswitch. The printing lamp comes on and the timer starts counting. I always step on the switch in time with the metronome. Count off the desired exposure. When complete, release the footswitch. Turn off the vacuum pump. Remove the paper and process.

Need to burn and dodge? Keep track of your exposure and use a card or cutout shape for the appropriate time. You can easily see the image since the paper is white and the negative is easily seen through the glass of the printing frame or vacuum frame.

Contact printing on Azo, or any other printing paper, is extremely easy, and is not rocket science. By adding the ability to print Azo using the 8×10 enlarger, we save space, which is always a premium in the darkroom. You can make your printing setup as simple, or complex as you desire. The main thing is to make prints. Make lots of prints. Those prints are what is important.

JB

JOBO IS BACK!

Good news for those of you that use Jobo products for processing in your wet darkroom. Posted on the Internet below from Firscall Photogaphic LTD, located in Taunton, Somerset, UK.

Jobo Announces first Film and Print Processor in over 20 years!

Posted on April 3, 2012 by Firstcall Photographic

Jobo stopped production of its rotary processors in 2010. In doing so it became the last manufacturer to market a range of film processing machines to photographers.

With the resurgence in demand for film usage, reduced mini-lab sites and film processing in multiple retailers, they have decided to re-tool to make a new film processor that will be available in the last quarter of 2012.

Based on the original design for the Jobo CPP2, the new model has the initial product code of CPP3 and will have the capability to process all types of film and paper. It will have accurate temperature control, timer and take all Jobo tanks up to the 3000 Expert (sheet film tank system). The original CPP2 concept will also be maintained in that it will have both cog and magnet lid connection for use with a lift and normal rotary agitation.

To get a technical Specification and a free £290 lift with purchase of the processor send your name and contact info to info@firstcall-photographic.co.uk

BEER & RODINOL

When I first began working with B&W in my own darkroom I only had a 35mm camera. So I shot many rolls of 36 exposure Tri-X. At one time my favorite developer was Rodinol. Not very expensive, easy to use, keeps forever and I liked the negatives. What else could you ask for?

Even way back then I kept a notebook with all of my darkroom procedures laid out in a step-by-step fashion. This way I knew I would always do things exactly the same. I used the same graduates, arranged in the same order every time. Developing film is a one shot deal. Make a mistake and that is all she wrote. At this point in my progression with film and darkroom, I had become confident in my ability to develop film. The process had become the first step on the way to making prints.

Even way back then I kept a notebook with all of my darkroom procedures laid out in a step-by-step fashion. This way I knew I would always do things exactly the same. I used the same graduates, arranged in the same order every time. Developing film is a one shot deal. Make a mistake and that is all she wrote. At this point in my progression with film and darkroom, I had become confident in my ability to develop film. The process had become the first step on the way to making prints.

My procedure for film was simple. I would line up my chemical containers in the correct order. Fill them with the proper liquids and adjust the temperature. Then I would head to my closet darkroom to load the film into the developing tank. I used a 16oz tank that held two reels and I usually did two rolls at a time. I loved the Rodinol because it came in a stock syrup and was mixed something like 1:200, if memory serves me correctly. I would measure the stock using two small syringes since it only took a few milliliters to make up the developer. I would lay the syringes, once loaded, next to the container marked developer which contained distilled water. I always have used presoak, so once the film was in the presoak, I would empty the syringes into the developer container and stir up the developer. Not much to it, simple and easy. Usually took me about forty five minutes from start to hanging up film to dry.

Now this one particular Saturday myself and a few friends went out and I shot two rolls of film that day. Later that evening we returned to my place for a few beers and by about 8:00 everyone headed home. I had this bright idea that if I processed the film from the day it would be dry and I could print it Sunday. Nothing to it, just get out the notebook, measure and slosh. . . processed film!

There was nothing very special about this film run, except the slight fog in my head from the beers and maybe a little to much sun. Everything went as usual. Once the film was washed I unrolled the first strip to find it completely clear end to end. The second roll was the same. What the @#$%^*? My first thought was the camera quit working. As I sat there perplexed I looked at my processing line and what do you think I saw? There next to the empty container for the developer lay my two syringes with the stock Rodinol still in them. I had failed to mix the developer. I learned right there that plain distilled water will not develop film. I also immediately enacted a strict rule in the darkroom; NEVER MIX RODINOL AND BEER!

JB

Even way back then I kept a notebook with all of my darkroom procedures laid out in a step-by-step fashion. This way I knew I would always do things exactly the same. I used the same graduates, arranged in the same order every time. Developing film is a one shot deal. Make a mistake and that is all she wrote. At this point in my progression with film and darkroom, I had become confident in my ability to develop film. The process had become the first step on the way to making prints.

Even way back then I kept a notebook with all of my darkroom procedures laid out in a step-by-step fashion. This way I knew I would always do things exactly the same. I used the same graduates, arranged in the same order every time. Developing film is a one shot deal. Make a mistake and that is all she wrote. At this point in my progression with film and darkroom, I had become confident in my ability to develop film. The process had become the first step on the way to making prints.MIXING YOUR OWN

I have always been an advocate of vertical integration. The more you can do yourself, the better control you have of the outcome. For many years I used prepackaged photo chemicals and have never had a problem. But, as the traditional darkroom and the materials used become more and more an alternative process, commercially available photo chemicals are getting harder to find. Some favorite chemicals have vanished. An old favorite, the Zone VI line of print developer, fixer and hypo are now gone from Calumet. I recently witnessed 8 bags of print developer and 2 bags of print and film fixer selling for $127.50 on eBay. That is well over double the original cost from Calumet.

I have always been an advocate of vertical integration. The more you can do yourself, the better control you have of the outcome. For many years I used prepackaged photo chemicals and have never had a problem. But, as the traditional darkroom and the materials used become more and more an alternative process, commercially available photo chemicals are getting harder to find. Some favorite chemicals have vanished. An old favorite, the Zone VI line of print developer, fixer and hypo are now gone from Calumet. I recently witnessed 8 bags of print developer and 2 bags of print and film fixer selling for $127.50 on eBay. That is well over double the original cost from Calumet.

The bottom line is, you can mix your own photo chemicals. Sometimes, if you purchase bulk raw chemicals, you can even save a few dollars. Another plus to mixing your own is the fact that you have 100% control. If something goes wrong, you know who to blame. You can also modify the formula and experiment. Mixing your own photo solutions is not hard. It is not rocket science and you do not have to be a chemist. If you can follow a recipe and bake a cake, you can mix your own chemistry for the B&W darkroom.

The first thing you need to understand is that in order to mix your own photo chemistry you will be handling CHEMICALS. If you are not comfortable with this thought, do not even go there. But, remember that you are surrounded with chemicals. . . the entire planet is made of them. If you take proper precautions and are careful, there is nothing to fear. I am not a chemist, so I have little understanding of deep details and I have even less inclination to study chemistry. Do as I do, assume that everything you handle in the way of raw chemicals are toxic. Do all mixing in a well-ventilated area. Clean up spills immediately. Avoid breathing airborne powders. Always wear gloves and purchase a respirator with proper filter. A little common sense goes a long way.

As I said before, for me, mixing photo chemicals is nothing less than following a recipe.

As I said before, for me, mixing photo chemicals is nothing less than following a recipe.

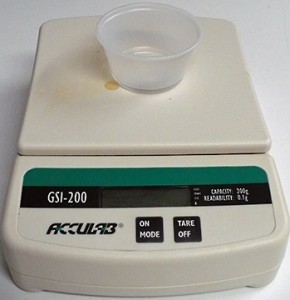

When mixing any photo chemistry formula/recipe you need to accurately measure all of the various chemicals. Most formulas call for dry chemicals measured in grams and liquids in milliliters. I have two scales for dry measure. I have a very accurate digital scale for small quantities and an old-fashion triple beam for larger amounts. I picked up a box of small serving containers at the local big box store to be used as disposable containers for measuring small amounts of dry chemicals. I also have larger 8oz plastic cups for larger amounts. Be sure to use the tare function to zero the scale with the empty container before measuring. Zero the scale with every new container, they do not all weigh the same. Once used, I toss them in the trash. I never reuse one of these plastic containers. This assures there is no chance of unwanted contamination.

For liquids, I use an appropriate size graduate, and for small quantities, a pipette is the easiest way to make accurate measurements. You can use a pipette pump to make loading and measuring easier, or just dip the pipette into the container and hold your thumb over the end. Remember to always thoroughly wash the pipette after use and always use a clean pipette when going from one chemical container to the next. If the pipette is not properly cleaned, you will cross contaminate your chemicals.

Always follow the chemical formula. Most all formulas are mixed in water and there should be a temperature specified to insure the chemicals dissolve. Always mix in the exact order as called for in the formula. Add each ingredient slowly and continually stir until each is completely dissolved before adding the next. This is where a magnetic stirrer comes in handy. Take your time. Do not rush the process. Some chemicals take some time to completely dissolve.

I use distilled water for all stock solutions. I always use distilled water for stock solutions and processing film. Unless your tap water has known problems, it should be fine for mixing printing chemicals.

I use distilled water for all stock solutions. I always use distilled water for stock solutions and processing film. Unless your tap water has known problems, it should be fine for mixing printing chemicals.

Once properly mixed, store each formula in a clean bottle with a plastic cap. Never use metal caps, some chemicals will cause them to rust and contaminate the solution. Brown glass is best for developers and plastic should be fine for most others. Be sure to label each container as to its contents and also include the date mixed. Most all stock chemicals are good for three months, some much longer.

There are many published formulas. Some popular commercial formulas are proprietary, but in many cases there are alternative, similar formulas that are published. By applying a little experimentation, you can tailor your photo mixtures to suit you. Search the Internet for formulas and pick up a copy of “The Darkroom Cookbook” Third Edition by Steve Anchell.

Mixing your own is not that difficult. With a little study, careful handling, forethought and experimentation you can mix your own photo chemistry.

Here is a list of things you will need or may want to have;

• disposable gloves

• respirator

• apron

• a selection of required chemicals

• accurate scales

• disposable plastic cups for weighing chemicals

• several sizes of graduates for liquids

• stirring rod

• magnetic stirrer

• pipette

• pipette pump

• glass storage bottles

• plastic storage bottles

Resources:

Bostic & Sullivan

http://www.bostick-sullivan.com

Artcraft Chemicals Inc.

http://www.artcraftchemicals.com

The Darkroom Cookbook Third Edition by Steve Anchell

http://www.steveanchell.com

Pyrocat HD a semi-compensating, high-definition developer, formulated by Sandy King.

http://www.pyrocat-hd.com

The Book Of Pyro by Gordon Hutchings

JB

CLEANING FILM HOLDERS

Dust is forever the biggest enemy of the large format shooter. Seems that no matter how meticulous you are, that one little speck of dust sneaks in and plants itself right in the middle of some nice smooth area. . . like the sky. It is a never-ending battle and requires continuous attention.

It is obvious that you need to keep your camera clean and it is imperative that you vacuum out all of your film bags and equipment cases. Dust gets everywhere, and it is good practice to vacuum everything before you go out to photograph. But, there is one area we have found to be extremely important for dust control, and that is keeping your film holders clean.

We have found that a thorough cleaning of every holder just prior to loading film keeps the dust problem to a minimum. If the inside of the holder is clean, then the outside is the only place where dust resides. Realize that the most critical time is before and during exposure. If a dust speck gets on your film after exposure, at least it is no longer a threat for making the dreaded pinhole which leads to the black spot on the print. After exposure, the worst a dust speck can do is possibly scratch the film during handling.

Everyone has their own methods for cleaning and loading film holders, and here are my main concerns and how we prepare our holders for loading. I will begin by saying that every holder is cleaned and inspected just prior to every loading session. Even on the road, we never load a holder with fresh film without cleaning. My biggest concern is dust inside the holder. I want the inside to be as clean, and dust free as possible. No matter how clean your film bags and cameras are, dust will always settle on the outside of the holders. If you thoroughly clean the inside of the holder, you will have a better chance of keeping the film dust free. I begin by cleaning the work surface with a damp towel and after dry I vacuum the area just to be sure. I always use the round brush on the end of the vacuum hose and before attaching I vacuum it well to make sure the bristles are free of dust.

I work each holder individually and begin by vacuuming the entire outer surface of the holder with the dark slide still in place. I pay particular attention to the entire area around the parameter of the holder where the slide meets the holder. I want the exterior of the holder as dust free as possible before I remove the slide.

One area that collects dust is the light trap area. Any dust on the dark slide will be wiped off by the felt in the trap. It is imperative that the dark slide be completely removed and the light trap vacuumed thoroughly. Also, while the dark slide is out of the holder, I vacuum the inside of the holder and the entire parameter, paying special attention to the film hold down and dark slide slots along the sides. I open the loading flap and vacuum under it also. The last thing I do before reinserting the dark slide is vacuum both sides of the slide and inspect it for dust or any possible damage. Each dark slide is removed, one-at-a-time, and always replaced in the same side of the holder. I never mix up slides, they always go back into the same holder and same side. . . always!

Once the holders are cleaned we immediately load them with fresh film and place them into their film bag. It is a good idea to vacuum the film bag before placing newly loaded film holders back inside. This is a good idea, especially if you have been in a particularly dusty area.

This is the ritual we go through every time we load film and we have little problems with dust on our film. Everyone has their own way of doing things and this is the procedure we use when loading film. There are a few things that we have found that greatly improve the odds of keeping your film clean. Remember, the vacuum is your best friend when it comes to dust. See my previous post titled “DUST. . . A Four Letter Word!” for more information.

JB

STOP & FIX WITH STAINING DEVELOPERS

As most know by now, we use staining film developers. To be specific, we use the classic PyroCat HD formula from Sandy King. This developer gives us the type of negative we like. Keep in mind that creating art, no matter what may be your chosen medium, is a very personal thing. What works for me may very well not be at all acceptable to you. My father used to say, “that is why they paint cars different colors.” Personally I do not care for red cars.

As most know by now, we use staining film developers. To be specific, we use the classic PyroCat HD formula from Sandy King. This developer gives us the type of negative we like. Keep in mind that creating art, no matter what may be your chosen medium, is a very personal thing. What works for me may very well not be at all acceptable to you. My father used to say, “that is why they paint cars different colors.” Personally I do not care for red cars.

All of that said, I have experimented with numerous staining developers and have chosen the one that works best for us. Along my journey of research I have found many opinions and myths that I have found to just not be true. Everyone seems to have an idea of what they believe to be true, but few have actually gone to the trouble to, as Fred Picker would say, TRY IT.

One area of great debate when it comes to staining developers is what stop and fix is appropriate. I find that this is not that great an issue and even John Wimberley agrees. Just in case you have not heard of John Wimberley, he is the father of modern Pyro developers. Even Gordon Hutchings the father of PMK, and author of “The Book of Pyro” was preceded by Wimberley and his first modern formula, WD2H. From an article titled “PyroTechnics Plus: Formulating a New Developer” in Photo Techniques magazine, March/April 2003, Wimberley has the following to say about Stop Bath and Fixer:

“Myths abound concerning the correct stop bath and fix to use with pyro, but it is not a critical issue. Either an acid or plain-water stop bath may be used, and any standard or rapid fixer is acceptable. . . However, avoid hardening fixers. I recommend the manufacturer’s minimum recommended time to avoid the possibility that sodium sulfite in the fixer might weaken the dye mask.”

Wimberley goes on to say that you should follow the manufacturer’s suggestion as to the proper stop for any type of fixer. If you use an alkaline fixer, use a plain water stop, or follow the instructions. He also says Hypo Clearing Agent (HCA) should not be used, since they are mostly sodium sulfite and “the enemy of the dye mask.” He recommends a 10 minute wash time in running water sufficient to complete five changes of water by volume.

If you do much research on this subject, you will find a lot of differing opinions. The thing is, you finally have to draw a line and choose what you intend to do with your processing procedures. So, having said that, here is the way I process film using PyroCat HD.

• Film is processed in open trays by the shuffle method

• Acid stop using 3ml 28% Acetic Acid plus 1,000ml water

• Fix in Kodak Rapid Fixer (no hardener)

• Rinse in running water 2-3 minutes

• Wash in a vertical washer 15-20 minutes

• Bathe in 2 drops wetting agent plus 1,000 ml distilled water

• Hang to dry

This is how I process film using my chosen staining developer. I am sure there are those that will point out all of the reasons this will not work, but I can assure you, it works for me. The most important thing to do is to be consistent. If you do things exactly the same every time, there is a very good probability that you will see consistent results. Fred Picker would say, “different is not the same.”

Remember, the best thing you can do is finalize your procedures and get on with creating your art. The finished print is what is important, how you get there should not get in the way of your creativity.

JB

• Acid stop using 3ml 28% Acetic Acid plus 1,000ml water

• Fix in Kodak Rapid Fixer (no hardener)

• Rinse in running water 2-3 minutes

• Wash in a vertical washer 15-20 minutes

• Bathe in 2 drops wetting agent plus 1,000 ml distilled water

• Hang to dry

EASILY FIND GRADE #2 AND GET YOUR FILM TEST CORRECT

So, here is the predicament; you are getting ready to do your film testing; you have decided to use the simple visual film testing technique. Visual film testing is a really simple way to determine your correct film EI and developing time. All you need to do is perform these tests on a grade #2 paper and you will know you are making the best possible negatives.

So, here is the predicament; you are getting ready to do your film testing; you have decided to use the simple visual film testing technique. Visual film testing is a really simple way to determine your correct film EI and developing time. All you need to do is perform these tests on a grade #2 paper and you will know you are making the best possible negatives.

>But, there is one nagging little problem. If you are using VC paper, how do you know what filter, or light source setting, that will produce a grade #2 contrast? Even if you are using filters, each filter set has different filters that will give different paper grades on different papers. Even the developer you choose can affect paper contrast. You really need to KNOW how to achieve a true grade #2, using your equipment and darkroom, in order to do a valid film test.

What if I could show you an easy, inexpensive, and quick method that will get you plenty close enough? Well, here you go. . . “FINDING VC PAPER GRADE #2; EYEBALL CALIBRATION.” This method should get you well within range to get you started on the right track.